Preprints

Table of Content

- A Cultural History of Heredity I

- A Cultural History of Heredity II

- A Cultural History of Heredity III

- A Cultural History of Heredity IV

- Heredity - The Production of an Epistemic Space

- The Hereditary Hourglass. Genetics and Epigenetics, 1868–2000

- Making Mutations: Objects, Practices, Contexts

- Graphing Genes, Cells, and Embryos

A Cultural History of Heredity I

____________________________________________________________________________________________

- Zoom

- Preprint - Heredity I, page 45.

Part of the Introduction

This volume assembles some of the contributions to the workshop “A Cultural History of Heredity I: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries” which took place at the Max-Planck- Institute for the History of Science MAY 24-26, 2001.

The workshop was the first in a series of workshops dedicated to the cultural history of heredity. There are a number of histories of genetics written from the perspective of history of ideas. François Jacob’s La logique du vivant (1970; engl. transl. 1973) and Robert Olby’s Origins of Mendelism (1966, 2nd ed. 1985) have certainly set lasting standards in this field. There are also some sophisticated, far from whiggish histories written from a disciplinary perspective, like Hans Stubbes Kurze Geschichte der Genetik (1963; engl. transl. 1972), Leslie Clarence Dunn’s A short history of genetics (1965), and Elof Axel Carlson’s The gene: a critical history (1966), to name just a few. What is missing, however, is a comprehensive study that embraces the cultural history of heredity by presenting the knowledge of heredity in its broader practical and historical contexts. In our project we wish to focus on the scientific and technological procedures, in which the knowledge of heredity was materially anchored and by which it affected other cultural domains. Such a project will be content neither with conventional history of ideas nor with mere social history. It will rather explore the various practices, standards, and architectures of hereditary knowledge and the “spaces” which they formed by their respective historical conjunctions. Heredity”, under this perspective, is more than the scientific discipline “genetics”. The project is less about the history of a science than about the history of a broader knowledge regime, in which a naturalistic conception of heredity developed historically that today affects all domains of society. This knowledge regime dates back to the social illusions and illuminations of the Enlightenment. What does it mean that nature determines history so that it appears as if history could be controlled by nature? And: are we today, with the advent of gene technologies, witnessing the end of a deterministic world view, or are we confronted with its definite restoration?

A project like this is vitally dependent on the participation of experts from a broad range of disciplines, covering cultural history in its various subdomains of science, technology, medicine, politics, economy, law, literature, and art. It will be pursued in a series of workshops, each focussing on a loosely defined “epoch” characterised by a certain development in hereditary knowledge.

The first workshop, organized by Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Peter McLaughlin and Staffan Müller-Wille, concentrated on the late seventeenth and the eighteenth century and assembled historians of science, medicine, politics and literature from the United States, Mexiko, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. Four poapers presented at this workshop make up this volume. Discussion during the workshop turned around two main questions: 1), if a concept of heredity existed at all in this period; and 2), in how far 18th century theories of generation were guided by empirical experience.

In regard to the first question, several contributions could show that there was no general concept of heredity underlying the discourse of the life sciences (Fantini, Terrall). However, there did exist some isolated, well-defined and sometimes, especially in breeding and medicine, highly localised fields structured by the recognition of hereditary transmission of differential characters 4 in the 18th century – the definition of specific difference in natural history (Müller-Wille), the explanation of hereditary diseases in pathology (Lopez-Beltran), political organisation of colonial societies according to racial characteristics (Mazzolini), and the application of hybridisation in plant (Ratcliff).

In regard to the second question, the workshop disclosed a rich spectrum of theoretical approaches to generation in the 18th century and made clear that this diversity is only insufficiently captured by the conventional dichotomy of preformation vs. epigenesis (Fantini, Terrall). This spectrum, however, was rather determined by different positions in regard to the politics and poetics of production, both experimental and social, than by a secured and welldefined domain of empirical data (Müller-Sievers, Roe, Terrall).

Complete citation:

Conference. A Cultural History of Heredity I: 17th and 18th centuries. Preprint 222. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2002.

A Cultural History of Heredity II

____________________________________________________________________________________________

- Zoom

- Preprint - Heredity II, page 70.

Part of the Introduction

The contributions to this volume were prepared for the second of a series of workshops dedicated to the cultural history of heredity. Concentrating in turn on a succession of time periods in chronological order, this series attempts to uncover and relate to each other the agricultural, technical, juridical, medical, and scientific practices in which knowledge of inheritance was materially anchored and in which it gradually revealed its effects. While the first workshop concentrated on the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the second dealt with a time period demarcated by two classical publications: Immanuel Kant’s Von den verschiedenen Rassen der Menschen (1775) and Charles Darwin’s The Variation of Plants and Animals under Domestication (1868).

One of the major results of the first workshop was corroborated by the contributions to the second, namely that no general concept of heredity was underlying the discourse on life (including medicine, anthropology and the moral sciences) in the eighteenth century and that such a concept was only slowly emerging in the first half of the nineteenth century. Carlos López Beltrán illustrates this in his contribution to this volume by directing our attention to a decisive linguistic shift: while the use of the adjective hereditary can be dated back to antiquity in the context of nosography (maladies héréditaires), a transition to a nominal use (hérédité) took place only from the 1830s onwards, first among French physiologists, then in other European scientific communities. This shift indicates a reification of the concept, or, in López Beltrán’s words, the establishment of a “structured set of meanings that outlined and unified an emerging biological conceptual space […] produc[ing] the first appearance of our modern concept of biological heredity.” For the fields of natural history and breeding one can recognise a similar shift from the use of adjectives like ‘constant’ and ‘true’ to refer to characters that remain unchanged in the course of generations, to the recognition of ‘heredity’ or ‘inheritance’ as one of the central life forces. Alongside this development, one can observe the erosion of a set of very ancient distinctions in regard to observed similarities between parents and offspring: the distinction of specific vs. individual, paternal vs. maternal, normal vs. pathological similarities all gave way gradually to a generalised notion of heredity capturing relations among traits independent of the particular life forms they were part of. This can be viewed as the main outcome of the first two workshops on the cultural history of heredity, to which all contributions, in one way or the other, attest. At the same time, however, this result provides the central, historiographical problem for our project. How is it that a phenomenon that, from a contemporary perspective, appears to be of central importance, and in its effects appears to be so tangible in everyday life, was subjected to conceptualisation so late? This seems to be the most curious feature of the cultural history of heredity: while ‘heredity’ today belongs to the most fundamental concepts of the life sciences, it entered the scenes of inquiry into the phenomena of life only very late in history. The late emergence of heredity coincides, moreover, with the important transformation that the life sciences underwent in general around 1800 and that Michel Foucault and François Jacob have described so succinctly. Though both of these authors focussed on the concept of organisation in studying this transformation, it seems highly probable that the emergence of heredity represents an aspect of utmost significance for fully understanding this transformation.

Complete citation:

Conference. A Cultural History of Heredity II: 18th and 19th centuries. Preprint 247. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2003.

A Cultural History of Heredity III

____________________________________________________________________________________________

- Zoom

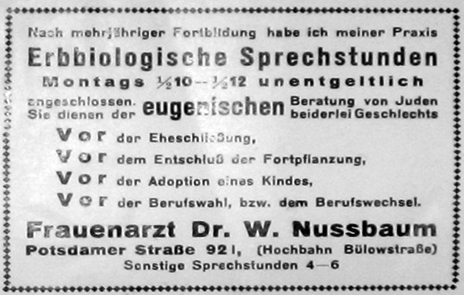

- Preprint - Heredity III, page 89.

Part of the Introduction

The contributions to this volume were prepared for the workshop “A Cultural History of heredity III: Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries” that took place at the Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science January 13-16, 2005. The workshop was part of a long-term interdisciplinary project dedicated to the cultural history of heredity. Concentrating in turn on a succession of timeperiods in chronological order, this series attempts to uncover and relate to each other the agricultural, technical, juridical, medical, and scientific practices in which knowledge of inheritance was materially anchored and in which it gradually revealed its effects. The two previous workshops took place in May 2001 and January 2003, each devoted to what we identified as ’historical epochs’ in the history of hereditary thought. What follows is a summary of the results reached so far in our project, of the questions we wanted to address with the third workshop, and the answers suggested to these questions by the contributions collected in this preprint.

In his book “The Logic of Life”, François Jacob already pointed out that the concept of reproduction, and by extension, that of heredity were virtually absent from speculations about generation until the eighteenth century. This we found largely corroborated. It may be worthwhile to stress that heredity as a biological concept originated as a metaphor: prior to the nineteenth century it was used as a synonym of “inheritance” in legal contexts only, a sense which it since then has lost. It was only in the early nineteenth century, in medical contexts, that metaphors of heredity began to gain currency. To be sure: Phenomena that nowadays would count as hereditary had by no means gone unnoticed before. It seems, however, to be a simple matter of historical fact that these phenomena were not addressed in terms of inheritance.

The conceptual reason for this was the lack of some fundamental distinctions in pre-modern theories of generation. Before the end of the eighteenth century hereditary transmission was not a domain regarded as separate from the contingencies of conception, pregnancy, embryonic development, parturition, and even lactation. Similarity between progenitors and their descendants was thought to come about as a result of the similarity in the constellation of causal factors involved in each act of generation. Parental organisms were thought to actually make their offspring, without the intervention of a specific hereditary substance transmitted from generation to generation.

So if speculations into generation did not provide the context in which biological heredity originated, what did? When Buffon, Maupertuis, and Kant were addressing heredity in the second half of the eighteenth century, they were referring, alongside the discourses of natural history and breeding, to a discourse of highly idiosyncratic origin, namely the Latin-American system of racial classification, known as las castas, and usually presented in paintings arranged in a tabular form. This scheme was primarily based on a classification according to skin color, to a lesser degree also on hair form and eye color. Children resulting from mixed marriages were positioned in this scheme in analogy to the simple mechanism of color mixing, implying “blending” as the causal relation connecting traits of parents with traits of their offspring.

Complete citation:

Conference. A Cultural History of Heredity III: 19th and early 20th centuries. Preprint 294. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2005.

A Cultural History of Heredity IV

____________________________________________________________________________________________

- Zoom

- Preprint - Heredity IV, page 207.

Part of the Introduction

This volume contains contributions to a workshop that was the fourth in a series of workshops dedicated to the objects, the cultural practices and the institutions in which the knowledge of heredity became materially entrenched and in which it unfolded its effects in various epochs and social arenas. It was organized collaboratively by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin, and the ESRC Research Centre for Genomics in Society, Exeter. Funds from the Academic Research Collaboration programme of the British Council and the German Academic Exchange Service allowed to prepare the workshop in two one-day-meetings of scholars from Berlin and Exeter. The workshop itself was funded by the British Academy and by the Government of the Principality of Liechtenstein.

The last workshop in the series had dealt with the period up until the very end of the nineteenth century when heredity had become a central problem for biologists and a wide variety of approaches to attack that problem had begun to flourish. The fourth workshop was specifically designed to address a historiographic problem that had arisen within the wider context of our project ‘A Cultural History of Heredity’. Up to the late nineteenth century, the knowledge of heredity took shape by a step-by-step aggregation and integration of discourses from various knowledge domains; while from 1900 onwards it began to condense into and to be shaped by a highly-specialized discipline, the discipline of genetics. This has resulted in a preoccupation of the historical literature with genetics. One of the basic assumptions of our project, however, has been that heredity was always and remained to be more than genetics as a discipline, and that wider notions of inheritance persisted in areas like practical breeding, medical counselling and therapy, eugenics, and anthropology (including cultural anthropology). To widen the scope of inquiry, we therefore decided to focus the workshop on the tools of dealing with inheritance, that is genealogical records and model organisms, and to follow their provenances, metamorphoses, and trajectories. The major results, as documented in this volume, can be summarized as follows.

Complete citation:

Conference. Conference A Cultural History of Heredity IV : heredity in the century of the Gene. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2008.

Heredity - The Production of an Epistemic Space

____________________________________________________________________________________________

- Zoom

- Preprint - The Production of an Epistemic Space, page 28.

Staffan Müller-Wille und Hans-Jörg Rheinberger

Biological heredity is the transmission of characters and dispositions in organic reproduction. From today’s perspective it appears to be of such paramount importance for the make-up of individual organisms and of such immediate and eye-catching evidence that it is hard to even imagine that there were times in which it did not occupy the centre of the life sciences. Yet until the end of the eighteenth century not only the concept of heredity but the very concept of reproduction was absent from speculations about living beings, as François Jacob remarked in his book La logique du vivant (1970):

Only towards the end of the eighteenth century did the word and the concept of reproduction make their appearance to describe the formation of living beings. Until that time, living beings did not reproduce; they were engendered. [...]. The generation of every plant and every animal was, to some degree, a unique, isolated event, independent of any other creation, rather like the production of a work of art by man.

There is a claim implicit to Jacob’s judgment that has been confirmed by other historians of biology time and again: Before the end of the eighteenth century and, according to some historians, even until the advent of Mendelism hereditary transmission was not a domain regarded as separate from the contingencies of conception, pregnancy, embryonic development, parturition, and even lactation.2 Similarity between progenitors and their descendants was thought to come about simply as a result of the similarity in the constellation of causal factors involved in each act of generation. It is in this sense that William Harvey, in his Anatomical Exercises on the Generation of Animals (1651), could maintain that the “work of the father and mother is to be discerned both in the body and mental character of the offspring, and in all else that follows or accompanies temperament”, while he simultaneously held the view that both “the male and female [are] merely the efficient instruments [of generation], subservient in all respects to the Supreme Creator, or father of all things.” As he went on immediately, taking up a thought of the “the great leader in philosophy”, Aristotle: “In this sense, consequently, it is well said that the sun and moon engender man; because, with the advent and secession of the sun, come spring and autumn, seasons which mostly correspond with the generation and decay of animated beings.” Inherited, connate, and acquired properties of organisms, the organic processes of transmission, embryonic development, and adaptation, in short: nature and nurture, heredity and environment – in the sense that these dichotomies should acquire with the end of the nineteenth century – were not distinguished in Early Modern notions of generation.

Complete citation:

Müller-Wille, Staffan and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger. Heredity - the Production of an Epistemic Space. Preprint 276. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2004.

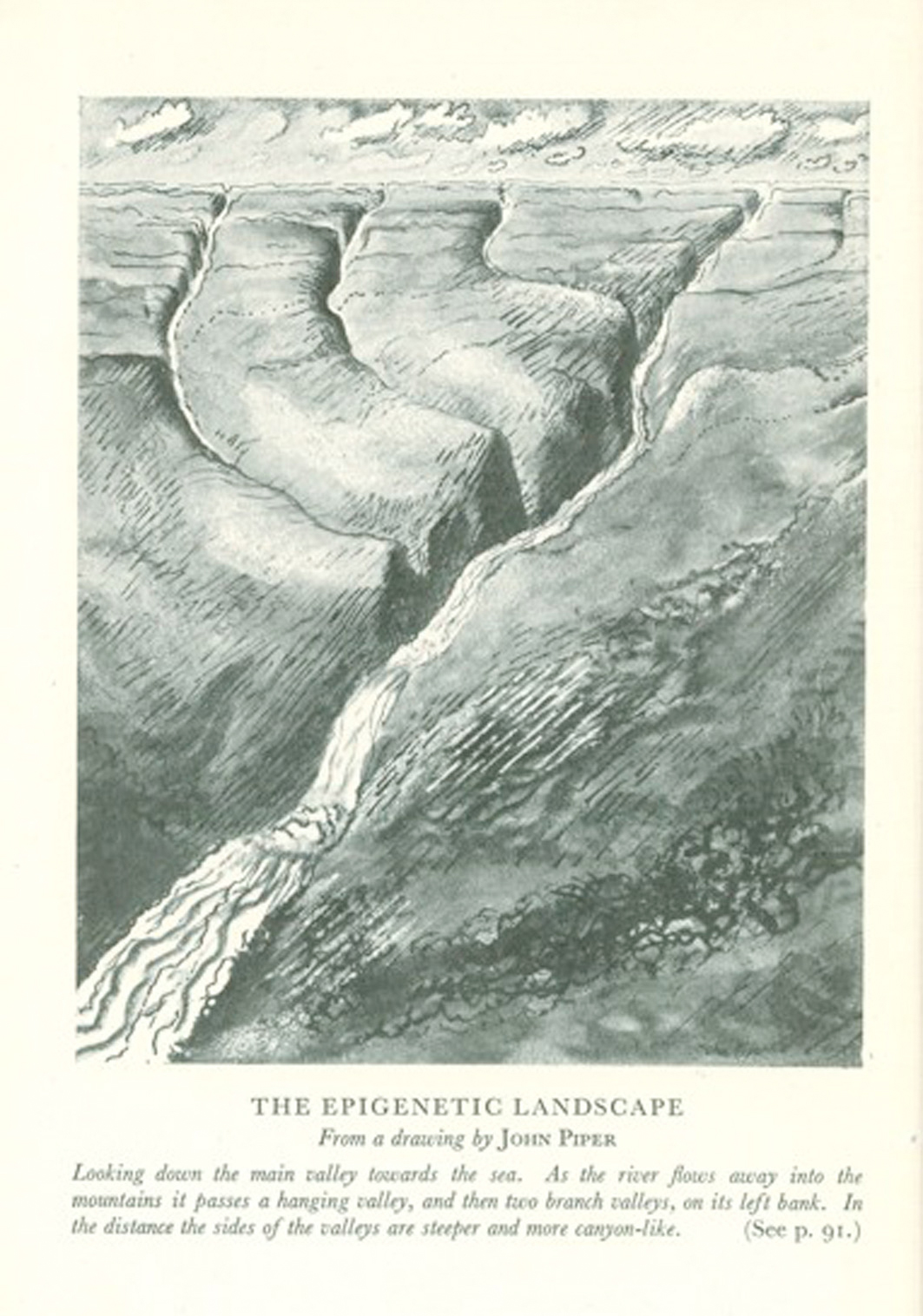

The Hereditary Hourglass. Genetics and Epigenetics, 1868–2000

____________________________________________________________________________________________

- Zoom

- Preprint - The Hereditary Hourglass, page 103.

Ana Barahona, Edna Suárez Díaz, and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, (eds.)

Over the past four decades the study of the phenomena of heredity has caught the attention of

historians, sociologists, and philosophers of the life sciences. Undoubtedly, this is reflected in the progress made to unravel the conditions under which the very idea of heredity came to fruition (Churchill 1987; López-Beltrán 2004; Müller-Wille and Rheinberger 2007), as well as in the informed accounts of different practices, tools (be they conceptual or material), and institutions identified with this field of inquiry. The challenge for the student of science is the same as when confronting other scientific endeavors, namely, the question of how to deal with the continuous research on the particularities of cases and specific problems, while simultaneously seeking to produce a broader picture on the field of heredity, within which isolated events acquire new meanings.

The questions students of science choose to ask may require both types of answers, the local

account and a more extended context. To keep them balanced has been our goal in this project. In order to combine both strategies we adopted the image of the hourglass or sand clock as a metaphor for the shape of the changes that have taken place in the wide-ranging studies of heredity – and some of its implications for the study of evolution –, from the second half of the 19th century up to the present day.

Complete citation:

Barahona, Ana, Edna Suárez Díaz, and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, eds. Hereditary hourglass: genetics and epigenetics 1868 - 2000. Preprint 392. Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2010.

Making Mutations: Objects, Practices, Contexts

____________________________________________________________________________________________

- Zoom

- Preprint - Making Mutations, page 3.

Luis Campos and Alexander von Schwerin (eds.)

This volume documents a recent workshop on the history of biological mutations in the twentieth century. How could such a seemingly limited topic fascinate twenty-two scholars from seven countries around the world for three days? One reason might be found in the image shown on the front page of our conference program: this image was deliberately presented without any identifying information about the shown plants, making it difficult to distinguish at a glance between “normal” and “mutant” plants. A trained eye — a mutant gaze — is needed. But such an assertion only seems to present still further epistemic challenges: is it ever truly possible to “see” a mutant or a mutation? A gene, conceived in one reductive sense as a stretch of chromosome, is arguably visualizable — at least in principle. A mutation, however, as a process — or as many geneticists might prefer to say, an event — seems still further removed from the phenomenal realm, popular incarnations to the contrary. If mutations are changes between past and present, and can only be inferred from observed phenomena that distinguish a normal organism from its mutated relative, provocative further questions emerge: who is doing the observing and the inferring? How do we know which is the mutant and which the original state? What does it mean to study mutants as the differences that make things visible?

Complete citation:

Campos, Luis and Alexander von Schwerin, eds. Making Mutations: Objects, Practices, Contexts. Preprint 393. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2010.

Graphing Genes, Cells, and Embryos

____________________________________________________________________________________________

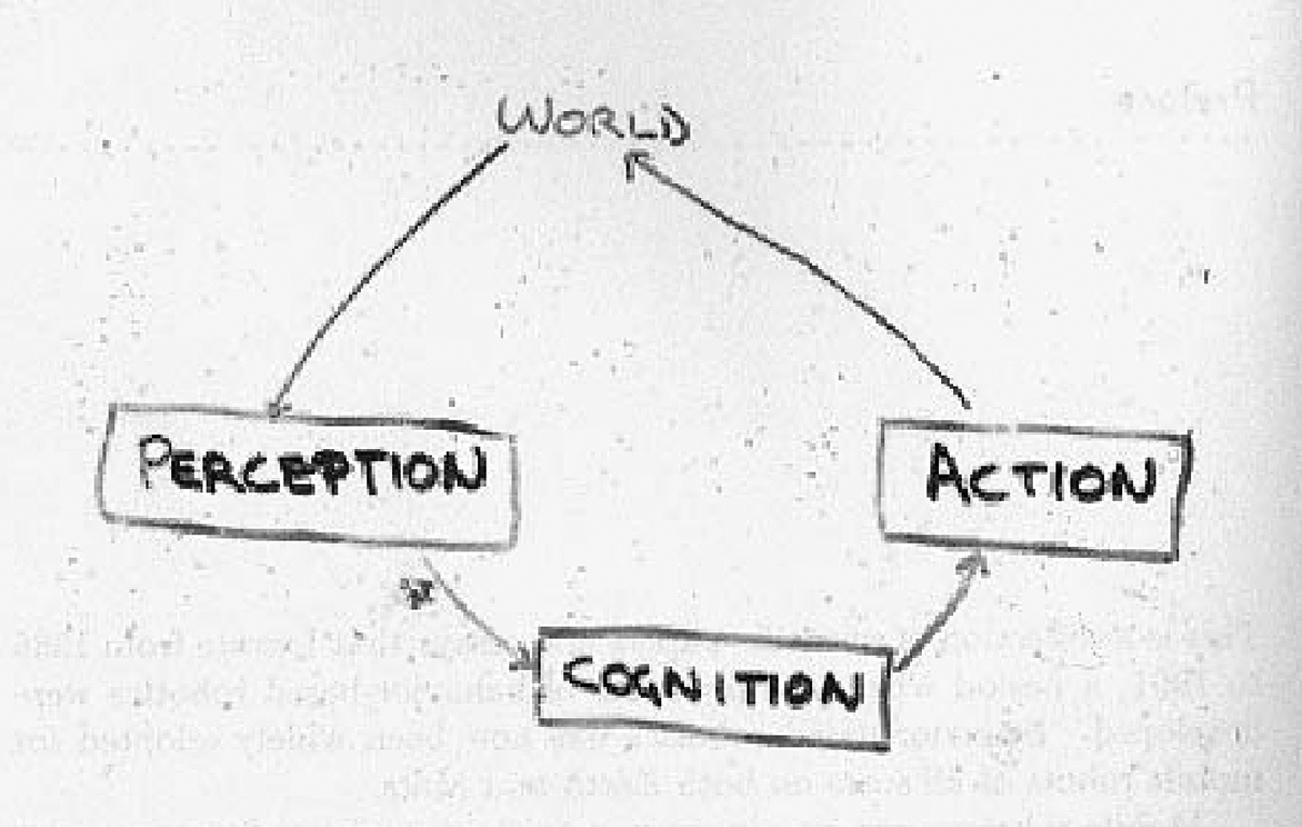

- Zoom

- Preprint - Graphing Genes, page 75.

Sabine Brauckmann, Christina Brandt, Denis Thieffry, Gerd B. Müller (eds.)

Biologists have always visualized their objects to a greater extent than physicists or chemists. Sincethe early 19th century, hand-drawings, professional illustrations, idealized diagrams, microphotography are extensively used, followed by time-lapse motion pictures in the 20th century, for visualizing the data and supporting one‘s own analyses. Nowadays, current visual practices encompass video and digital imaging, including virtual dissections and rotating panoramas of embryonic features. In general, these scientific images are means to store and exchange experimental data and to generate specialized knowledge of biological objects. The objects can be individuals, like an embryo or egg, cells, biomolecules, or yet sets of animals or plants. In contrast with physical entities, they are visually flexible phenomena, whose boundaries,extension and identifying details are studied to explain dynamical structures and processes likeembryogenesis, cell morphologies, or biomolecular networks.

To capture this visual specificity of the life sciences, the BioGraph workshop series focuses on elaborated analyses of how the life sciences visualize and represent their objects of study. At the first Workshop held in Naples in May 2007, we analyzed (1) the biological material considered in priority, e.g. embryos, cells, and genes; (2) the type of graphical representations used, e.g. fate maps, cell lineages, or gene networks; and (3) the techniques employed to construct these graphs, e.g. hand drawings, diagrams, tables, micro-photographs, time-lapse motion pictures, or computer imaging. Our objective was to disclose the production of biological knowledge on embryos, cells, and genes, from the early 19th to in silico biology, by comparing the graphic models of classical disciplines evoking lifelike images within the mind, from embryology and cytology to most recent computer imaging techniques. We further elucidated in detail which experimental procedures schooled the scientists to coordinate eyes and hands when redrawing over and over again images of cells pushing against each other, or fixing the boundaries of embryonic layers, permanently moving and shifting their position inside an embryo.

Complete citation:

Brauckmann, Sabine, Christina Brandt, Denis Thieffry and Gerd B. Müller, eds. Graphing genes, cells, and embryos: cultures of seeing 3D and beyond. Preprint 380. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, 2009.

Heredity

Heredity